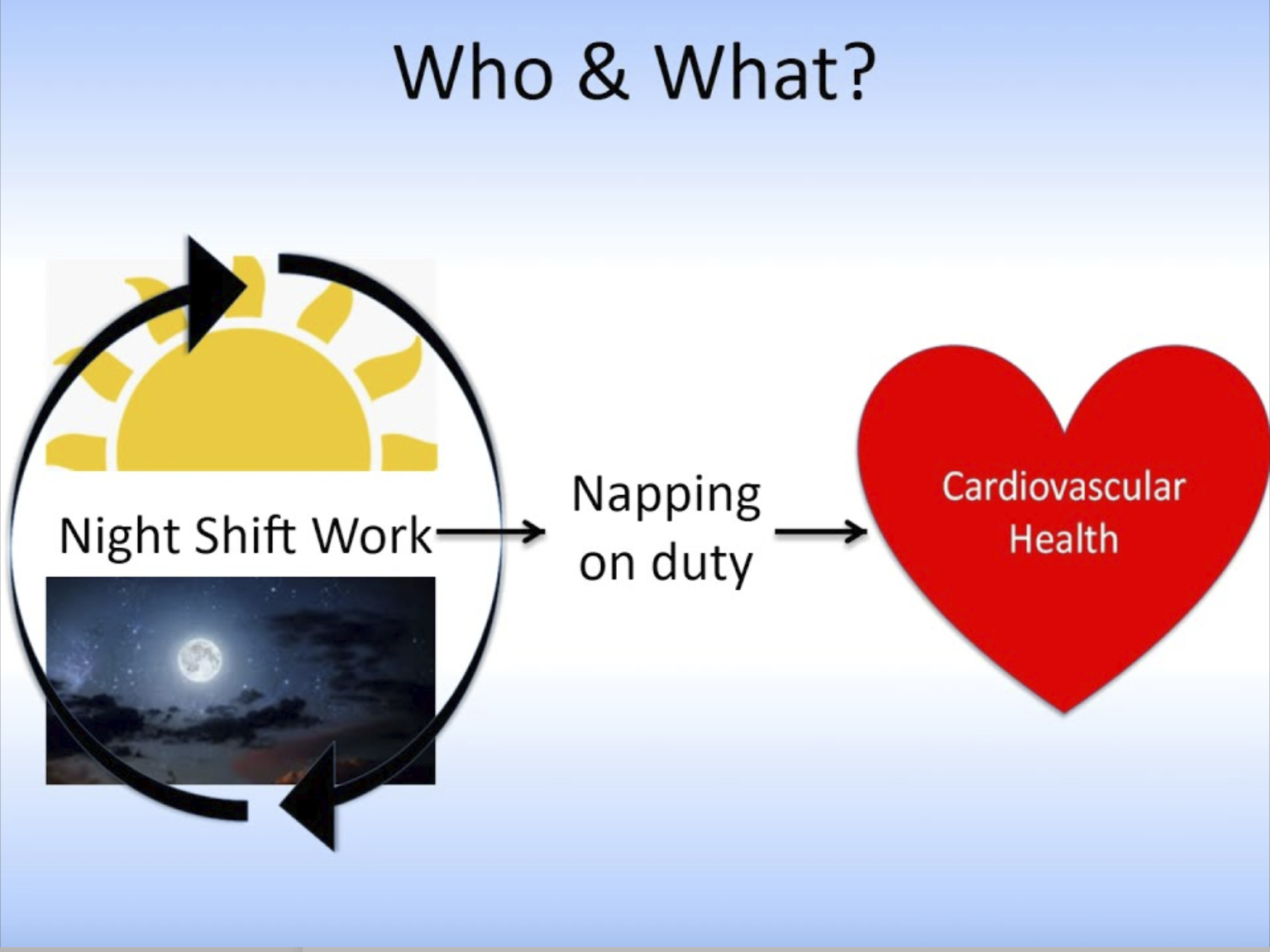

Night shifts often entail working past midnight into the early morning hours and is a common feature of shift schedules for most in Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and other sectors of public safety.

For those in EMS who frequently work night shifts on a regular basis, or occasionally on a rotating schedule, fatigue and daytime sleepiness are common – especially during the early morning hours. Fatigue related to shift work can carry over into the post-shift work period and impact how alert, sleepy, and fatigued one feels during the first 24 hours post-shift – the recovery period, which sometimes does not feel much like recovery.

Shift work is not going away. Our society operates 24 hours-a-day and emergencies are not scheduled. All who work in public safety, including EMS, understand that we must be available at all hours and quickly respond to the needs of the acutely ill and injured. Fatigue is a common consequence of shift work because it disrupts the habitual circadian pattern of staying awake during the day and sleeping at night. Sleep deprivation associated with night shift work also disrupts the normal pattern of blood pressure (BP), which encompasses elevations during the day and during wake followed by a 10-20% decrease (dip) during sleep and nighttime hours. Some research links disruption of this dip (referred to as blunting) to numerous negative cardiovascular related outcomes.

Recent research out of the University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Emergency Medicine shows that napping during night shifts can help to restore the normal circadian pattern in BP. Napping during night shifts and long duration shifts is supported by the best available evidence and is part of a set of recommendations that comprise the 2018 Evidence Based Guideline for Fatigue Risk Management in EMS. A recent observational study shows that longer duration naps (such as 1-hour or longer) are associated with restoration of the BP dip in most EMS clinicians who take a nap. An ongoing experimental study is testing different duration naps in a laboratory setting to determine if shorter duration naps (such as 30 minutes) allow for restoration of the normal dip in BP during sleep and nighttime hours.

While the lab-based study is ongoing, current data supports napping as a tool to not only help restore normal BP patterns, but it has also been shown to reduce sleepiness and fatigue. The main takeaway – based on the best available evidence – if you are allowed to nap on night shifts – DO IT!

P. Daniel Patterson, PhD, NRP

Associate Professor

James O. Page Professor of Emergency Healthcare Worker Safety

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Pittsburgh